The radical yet obvious way to make college sports coaches better

The answer's been right in front of them all along

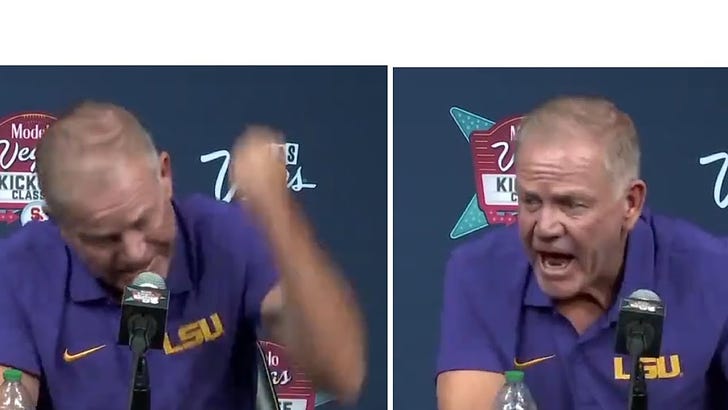

Brian Kelly makes $9,500,000 annually to coach Lousiana State University’s football team. Last weekend, his team led late but ultimately fell 27-20 to the University of Southern California. Kelly made it clear postgame this loss is stuck good and tight all up in his craw.

He just cares so much about winning! So much so it’s practically bursting out of his pores, as if he’s biologically compelled to prove beyond any shadow of a doubt just how much he hates losing. How pathetic.

And yet it’s common to the point of cliche, the cantankerous coach trope. There aren’t many professions where it’s considered normal and even healthy for grown adults to meltdown like toddlers.

Maybe performativity is unavoidable when you make insanely unjust amounts of money. A parodying of penance. We know they don’t deserve it. They know. We know they know, and they know we know they know.

Anyone who works with dozens and dozens of 17-22 year olds — or anyone who’s ever been part of any group of humans, or ever imagined one — grasps the stupidity of expecting the same energy from them every time they meet. And yet college coaches in particular struggle with this truth. They seem very, very stressed about some of the most basic parts of their job. Like games. They freak out during games!

Turns out there’s a simple solution to maturing these old babies. Any coach earning $1,000,000 or more a year should have to do an independent study with an adjunct writing professor.

Think of it like weight-training: using resistance to build muscle memory. Coaches have way more power and money than their players, yet appear so insecure when they rant and rage. There’s a kind of built-in laziness for them, whether they’re aware of it or whether they seek to exploit it or not — the power imbalance between them and their players is chasmatic. They need to come down a few pegs. It’s good for them and their workspace.

I, a humble adjunct writing professor, work with classes where the majority of students drive a nicer car than me. Hell, my car is older than some of my students. None of them are in my class by choice; many of them enter the semester thinking of writing as a thing to endure for a few months and then relegate to their memory’s trash bin.

And while professors are often placed above their students in a university’s hierarchy, we don’t have power over scholarships or potential future income via name, image & likeness rights, or the possibility of a pro career. A student once wanted to know why I failed their essay. After I went over essay-, paragraph- and sentence-level problems with it, they told me “I think it’s actually really good.” Try that line with a red-faced profanity-spewing coach and see where it gets you.

Games are basically sports exams. Can you imagine taking a test, getting something wrong and having your instructor scream at you? The first semester I taught, I asked a class what was the longest military conflict in American history. The first answer was “the Crusades.”

I didn’t punch the lectern. The student didn’t need his classmates to hold me back from attacking him. It was a teaching moment, an opportunity to go over stuff with them that they’d clearly never had before. Something they needed, and that I, ostensibly, could provide. Having coaches observe adjuncts would make them better communicators and teachers. Isn’t that what they get the big bucks for? It’d be an investment in better practice. In such a highly competitive and well-funded field, every edge counts.

Ideally, games should be treated like exams. I spend weeks getting my kids ready for a paper or a test, but when it’s time to put up or shut up they’re on their own. I’m no longer involved. Coaches should work with players in practice, but when it’s time for a game, meet or match they shouldn’t be around. If they’ve done their job — done it completely and holistically — the proof should be in the pudding of the players’ play. The point of teaching anyone anything is to elevate them to where the student becomes the master. That kind of leveling up only comes from self-motivation; the self-motivated student is the educational version of Neo becoming The One.

The next time you see a college coach behaving in a way you’d never accept from someone, think of all those vast untapped fields of overqualified, underpaid adjuncts, from sea to shining sea. Think of the mutualism: pay adjuncts a fraction of what coaches get and that’s life-changing money, while coaches who emphasize differentiation and sustainable assessments over bulging eyes and a hoarse voice from yelling will blaze a more humane and well-taught trail. All while still making more than more than more than more than more than more than enough money.